Could a Band-Aid-sized $100 ultrasound transducer be coming soon?

por John W. Mitchell, Senior Correspondent | September 13, 2018

Ultrasound

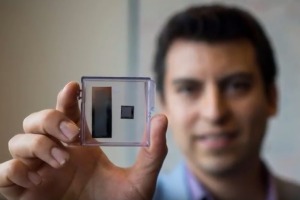

Engineers at the University of British Columbia (UBC) have successfully fabricated a Band-Aid-sized, flexible ultrasound transducer that produces images as detailed as traditional sonograms. Powered by a smartphone, their prototypes have the potential to lower the cost of an ultrasound to around $100.

“Ultrasound is the number one medical imaging modality in the world; it is very safe and noninvasive," Carlos Gerardo, Ph.D. candidate in the university's Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering and one of the project team members, told HCB News. “Nevertheless, high-quality ultrasound systems like the ones in hospitals are very expensive. So we thought about a way to create high-quality ultrasound transducers at a reduced price.”

The team’s research was just published in Nature Microsystems & Nanoengineering.

To accomplish their goal, the team replaced the conventional piezoelectric transducers used in ultrasound for the past 60 years with new drum-based capacitive micromachined ultrasonic transducers (CMUT) technology using low-cost polymer-resin materials. This resulted in a simple fabrication process to create high-quality transducers for a just a few dollars.

To accomplish their goal, the team replaced the conventional piezoelectric transducers used in ultrasound for the past 60 years with new drum-based capacitive micromachined ultrasonic transducers (CMUT) technology using low-cost polymer-resin materials. This resulted in a simple fabrication process to create high-quality transducers for a just a few dollars.

The early prototypes took six months to turn around using a Silicon Valley fabricator, according to Gerardo. Part of their breakthrough came when the team brought the fabrication in-house, which allowed them to design, build and test a new design in one day using green alternative microfabrication technology.

When asked about the device's potential, Gerardo cited their initial findings. Sonograms produced by the device were as sharp as or even more detailed than traditional sonograms generated by standard ultrasound transducers.

“Skeptics would be wise to ask about specific performance metrics such as sensitivity, durability, and stability,” Gerardo said. “The results we have gotten so far seem very promising.”

He added that their working prototypes had run a limited number of tests and they need to expand to include practical tests for clinical use. For example, miniaturized traducers could examine inside arteries and veins or monitor the heart in real time.

Gerardo also cited the low power features that could open the door for many other applications, such as in the wearable electronics industry. The UBC device can operate on just 10 volts, making it suitable for use with a smartphone.

“We want to emphasize that our invention is not just giving better performance/price ratio. The polymer-based CMUT has other potential features and advantages worth exploring,” said Gerardo. “[These include] fabrication on flexible substrates, low voltage operation, low-temperature fabrication directly on electronic circuits, optical transparency, biocompatibility, and greener fabrication. All of these will be explored.”

“Ultrasound is the number one medical imaging modality in the world; it is very safe and noninvasive," Carlos Gerardo, Ph.D. candidate in the university's Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering and one of the project team members, told HCB News. “Nevertheless, high-quality ultrasound systems like the ones in hospitals are very expensive. So we thought about a way to create high-quality ultrasound transducers at a reduced price.”

The team’s research was just published in Nature Microsystems & Nanoengineering.

Quality, speed, and peace of mind

GE HealthCare’s Repair Center Solutions are an ideal complement to your in-house service team. We service a broad range of mobile devices, including monitors and cardiology devices, parts, and portable ultrasound systems and probes.

The early prototypes took six months to turn around using a Silicon Valley fabricator, according to Gerardo. Part of their breakthrough came when the team brought the fabrication in-house, which allowed them to design, build and test a new design in one day using green alternative microfabrication technology.

When asked about the device's potential, Gerardo cited their initial findings. Sonograms produced by the device were as sharp as or even more detailed than traditional sonograms generated by standard ultrasound transducers.

“Skeptics would be wise to ask about specific performance metrics such as sensitivity, durability, and stability,” Gerardo said. “The results we have gotten so far seem very promising.”

He added that their working prototypes had run a limited number of tests and they need to expand to include practical tests for clinical use. For example, miniaturized traducers could examine inside arteries and veins or monitor the heart in real time.

Gerardo also cited the low power features that could open the door for many other applications, such as in the wearable electronics industry. The UBC device can operate on just 10 volts, making it suitable for use with a smartphone.

“We want to emphasize that our invention is not just giving better performance/price ratio. The polymer-based CMUT has other potential features and advantages worth exploring,” said Gerardo. “[These include] fabrication on flexible substrates, low voltage operation, low-temperature fabrication directly on electronic circuits, optical transparency, biocompatibility, and greener fabrication. All of these will be explored.”

You Must Be Logged In To Post A CommentRegistroRegistrarse es Gratis y Fácil. Disfruta de los beneficios del Mercado de Equipos Médicos Nuevos y Usados líder en el mundo. ¡Regístrate ahora! |

|