Los científicos consiguen más cercano a jab universal de la gripe

por Brendon Nafziger, DOTmed News Associate Editor | July 16, 2010

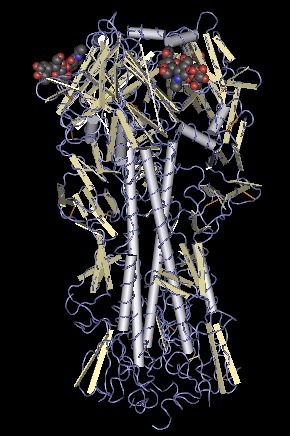

Antibodies target the stem

of the flu protein hemagglutinin.

of the flu protein hemagglutinin.

Scientists have inched closer to the "holy grail" of flu researchers: a universal flu vaccine. Because the flu virus mutates so rapidly, vaccines are quickly outdated and most people need to get a new shot every year. But scientists working with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases have created a DNA-based vaccine that appears to protect animals against multiple strains of the virus, some almost 70 years old.

In a study published online Thursday in Science Express, government scientists say they've created a vaccine that uses periodic boosters to train the immune system to fight multiple strains of influenza. The scientists hope this new approach could lead to a treatment of influenza that's more in line with inoculation series against other viruses.

"The prime-boost approach opens a new door to vaccinations for influenza that would be similar to vaccination against such diseases as hepatitis, where we vaccinate early in life and then boost immunity through occasional, additional inoculations in adulthood," Dr. Gary J. Nabel, lead author of the study and a researcher with NIAID, said in a statement.

In the study, the researchers gave mice, ferrets and monkeys a vaccine made from DNA encoding a special influenza protein called the hemagglutinin surface protein, derived from a flu virus circulating in 1999. After being primed with this shot, the animals later got a booster dose of 2006-2007 flu vaccine. Some mice and ferrets also got a booster vaccine made from a weakened form of adenovirus, a virus that can cause colds, also carrying flu hemagglutinin.

The scientists said the combination of the two jabs helps animals create antibodies against the stem of hemagglutinin, a lollipop-shaped protein that helps the flu virus stick to cells. The head of the protein mutates all the time, so it quickly becomes unrecognizable to antibodies. But the stem varies little from strain to strain, so antibodies against the stem should recognize many strains of flu, the scientists reasoned.

In the study, mice and ferrets produced antibodies against strains in 2006, 2007 and even as far back as 1934, even though they were only really inoculated against the 1999 strain. The animals also produced antibodies against H5N1, the avian flu virus, despite only being protected against H1 subtypes of influenza A.

The prime-boost and prime-cold strain combos also protected the animals in direct tests of their immunity to the virus. In one leg of the study, the researchers gave 20 mice that had the prime-boost vaccines large amounts of the 1934 flu virus. Eighty percent of them survived, whereas none of the mice exposed to the virus that just had seasonal vaccine, or just the DNA-based vaccine, lived. A similar test on ferrets found the combo vaccines protected them from the 2007 and 1934 strains.

So how far away is this from the clinic? Early safety trials on similar vaccines in humans are already underway, the NIAID said.

"We may be able to begin efficacy trials of a broadly protective flu vaccine in three to five years," Dr. Nabel said.

In a study published online Thursday in Science Express, government scientists say they've created a vaccine that uses periodic boosters to train the immune system to fight multiple strains of influenza. The scientists hope this new approach could lead to a treatment of influenza that's more in line with inoculation series against other viruses.

"The prime-boost approach opens a new door to vaccinations for influenza that would be similar to vaccination against such diseases as hepatitis, where we vaccinate early in life and then boost immunity through occasional, additional inoculations in adulthood," Dr. Gary J. Nabel, lead author of the study and a researcher with NIAID, said in a statement.

In the study, the researchers gave mice, ferrets and monkeys a vaccine made from DNA encoding a special influenza protein called the hemagglutinin surface protein, derived from a flu virus circulating in 1999. After being primed with this shot, the animals later got a booster dose of 2006-2007 flu vaccine. Some mice and ferrets also got a booster vaccine made from a weakened form of adenovirus, a virus that can cause colds, also carrying flu hemagglutinin.

The scientists said the combination of the two jabs helps animals create antibodies against the stem of hemagglutinin, a lollipop-shaped protein that helps the flu virus stick to cells. The head of the protein mutates all the time, so it quickly becomes unrecognizable to antibodies. But the stem varies little from strain to strain, so antibodies against the stem should recognize many strains of flu, the scientists reasoned.

In the study, mice and ferrets produced antibodies against strains in 2006, 2007 and even as far back as 1934, even though they were only really inoculated against the 1999 strain. The animals also produced antibodies against H5N1, the avian flu virus, despite only being protected against H1 subtypes of influenza A.

The prime-boost and prime-cold strain combos also protected the animals in direct tests of their immunity to the virus. In one leg of the study, the researchers gave 20 mice that had the prime-boost vaccines large amounts of the 1934 flu virus. Eighty percent of them survived, whereas none of the mice exposed to the virus that just had seasonal vaccine, or just the DNA-based vaccine, lived. A similar test on ferrets found the combo vaccines protected them from the 2007 and 1934 strains.

So how far away is this from the clinic? Early safety trials on similar vaccines in humans are already underway, the NIAID said.

"We may be able to begin efficacy trials of a broadly protective flu vaccine in three to five years," Dr. Nabel said.