por

Brendon Nafziger, DOTmed News Associate Editor | December 13, 2010

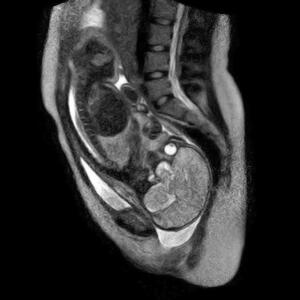

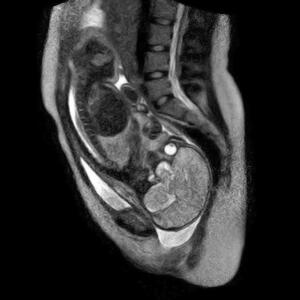

Live birth caught

on MRI (Image courtesy

Philips Healthcare)

Radiology news from around the world for Dec. 13, 2010.

MRI captures baby's first moments

For the first time, an MRI scan captured a baby's live birth.

Ad Statistics

Times Displayed: 16169

Times Visited: 33 Final days to save an extra 10% on Imaging, Ultrasound, and Biomed parts web prices.* Unlimited use now through September 30 with code AANIV10 (*certain restrictions apply)

Doctors at the Berlin's Charité University Hospital in Germany recorded a baby entering the world using an open high-field MRI scanner developed by Philips Healthcare.

The opened-up scanner doesn't have a typical tube shape, so doctors could have access to mother and child during the birth, Philips said.

The researchers said they spent more than two years trying to perfect the device, and had to also create a special fetal surveillance monitor that wouldn't be compromised by the intense magnetic fields generated by the magnet.

And Philips said the scan isn't just a novelty: the research team, made of radiologists, obstetricians and equipment specialists, wants to use live birth imaging to learn why in about 15 percent of all births there is stalled labor requiring a Cesarean section.

Czech rads investigate 400-year-old mystery

Czech radiologists think CT scans of a famous astronomer could help solve a nearly 400-year-old mystery.

Radiologists from the Na Homolce in Prague are helping Danish researchers uncover how 16th century astronomer and astrologist Tycho Brahe died, Prague Daily Monitor reports.

The radiologists said they have scanned about 25,000 narrow profiles of the exhumed remains, and are creating 3-D models which they will send to Denmark for further analysis. The Danish researchers hope to use the findings to get clues about Brahe's height and health at the time he died.

Most schoolchildren know the official story: at a banquet, Brahe (1546-1601) drank copious amounts of alcohol, but thought it impolite to leave the table to urinate. Eleven days later, he died, possibly of a bladder or kidney problem (though scientists have long since squashed the idea he died from a burst bladder).

However, hairs from Brahe tested in the 1990s revealed the great scientist likely had been exposed to high levels of mercury, leading some to speculate that he had been poisoned. Numerous suspects have been named, including his assistant Johannes Kepler, the astronomer who helped birth the Scientific Revolution. Supposedly, Kepler wanted to prove his model of the universe, but needed to lay his hands on some of Brahe's observations of Mars, which Brahe refused to share with him. Other potential plotters include Brahe's cousin and even the king of Denmark, angered over gossip Brahe was having an affair with his mother.