Brazil lures medical equipment makers

January 01, 2012

by Brendon Nafziger, DOTmed News Associate Editor

Brazil’s growing economy makes it attractive to device makers, but the country is off-limits to secondhand dealers.

You probably have never heard of Contagem, Brazil, an industrial town of some 627,000 souls about 277 miles north of Rio de Janeiro. But there, on July 22, 2010, GE Healthcare opened its first factory in South America.

For now, the plant is making an X-ray system that’s meant to be sold throughout the continent. Soon though, GE also hopes to produce higher-end equipment at the factory, including PET, CT and MRI scanners.

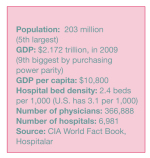

GE isn’t alone in moving to Brazil. Manufacturers of all kinds are headed there, hoping to gain a foothold in the world’s fifth most populous country. After all, Brazil has 400,000 hospital beds. The patients filling those beds are, increasingly, a bit older and a bit richer, and they want access to the same top-flight medical devices the developed world takes for granted.

For foreign companies, this vast nation – the world’s ninth largest – is attractive for many reasons. For one, it has weathered the economic doldrums better than most developed countries, with its gross domestic product forecasted to grow around 4 percent this year, according to Espicom, a market research firm. For another, the market is huge: the biggest for medical devices in Latin America, and the largest private insurance market, aside from the United States, in all of the Americas.

True, compared to the United States, the amount spent on health care per person is low — roughly one-tenth what it is here. Per capita health expenditures are $734, compared with $7,410 per capita in the U.S. (2009 figures), according to the World Bank. Health care accounts for 8 percent of Brazil’s GDP —slightly less than half of what it is in the U.S. Life expectancy at birth is also lower — 73 for Brazil versus 78 for the U.S., much of it owing to tragically high infant mortality rates, especially in rural areas.

In fact, the rural-city divide characterizes much of Brazil’s health care system. Brazil’s partly public system, on which much of its populace relies, has a low doctor-to-patient ratio, especially in the countryside. But Brazil is committed to modernizing its health infrastructure. And with growing wealth, the private sector is increasing in scope. Nearly every month, a brand-spanking new facility pops up, or a hospital announces it has outfitted a new surgical suite or imaging center, with many of these developments tracked by Hospitalar, an organization that runs a yearly conference on health care and hospital business in the country. In December, for instance, Hospitalar reported that 11 private hospitals in São Paulo were receiving $1.4 billion in investments over the next five years. One of these hospitals, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, plans to spend half a billion dollars over the next two years to expand its main facility and open a new branch.

Manufacturers see opportunity

The growth is borne out by the numbers. Between 2003 and 2006, Brazil’s diagnostic imaging and monitoring equipment market grew 20 percent per year, while in the rest of the world it only grew 4 to 5 percent per year, Steve Rusckowski, CEO of Philips Medical Systems, explained in a statement a few years ago.

How big is the market? It depends on who’s reporting the numbers. Estimates for Brazil’s medical device market are around $3.6 billion to $4 billion, according to two Espicom reports from this year. Imports total about $1.8 billion, according to Espicom, although Hospitalar puts that figure much higher ($3.65 billion).

As expected, the country mainly relies on imports for high-tech equipment that can’t be made locally, with the majority of that equipment coming from North America or Western Europe.

Of course, exporting to Brazil isn’t the only path for making inroads into the economy. Companies like GE are making investments locally too. GE’s Contagem factory, for instance, will cost the company $50 million over the next 10 years. GE Healthcare’s parent business also plans to open a massive Global Research Center in Rio de Janeiro next year.

Other manufacturers are planting roots in Brazil. Philips has purchased a number of local businesses to expand its influence there. Last year, it bought Wheb Sistemas, a clinical informatics systems company. In 2008, it bought Dixtal Biomédica e Tecnologia, a maker of patient monitors used in hospitals. But one of its biggest moves was in 2007, when it bought the country’s largest X-ray manufacturer, VMI-Sistemas Medicos, as part of a plan to seize on emerging markets that had been in the works since the previous year. In 2008, the company also opened, in Brazil, the first plant for making MRIs in all of Latin America, according to Espicom.

Siemens Healthcare also says it plunked $50 million in the country last year. Siemens, which says it employs 10,000 people in the country, also intends to invest $600 million in business activities there over the next five years, according to an interview between health care division’s global CEO Hermann Requardt and the Brazilian daily paper DCI. For the past 10 years, Siemens has made the MULTIX B X-ray system in the country, and sold about 750 units, he said in the interview. Now, nearly a third of all digital diagnostic imaging in Brazil is performed on its equipment, Requardt said.

Used dealers need not apply

Although a big market, and one that is “value-conscious” when compared to the U.S. or other developed countries, Brazil is surprisingly off-limits to one class of sellers: used equipment dealers.

In a recent report, the Commerce Department placed Brazil on its list of 16 countries that in some cases have restrictions "so severe as to be tantamount to a prohibition." Thanks to regulation passed in 2001, the RDC 25/2001, in order to be imported into Brazil, used devices must be registered, licensed and refurbished back to original manufacturer specifications, as well as passed through local quality control tests.

"OEMs can bring their products to Brazil easily, such as Phillips, GE, Siemens, since they have a better control on how to refurbish [that] equipment," an official who works with the Commerce Department told DOTmed News earlier this year. "One of the main regulations is that the company that will export to Brazil must have an authorization from the OEM to sell in our country. But even this way, this is still a difficult procedure."

And while Brazil has allowed refurbished equipment to be imported, even that is changing. Carlos Goulart, the head of trade group Abimed, told DOTmed News that Anvisa, Brazil’s equivalent of the Food and Drug Administration, is worried that even refurbished devices aren’t safe. This summer, Anvisa floated a proposal that would completely ban refurbished imports. In acknowledgement of the proposal, the public sent Anvisa almost 1,000 responses, Goulart said. But it seems nothing will sway them. Last week, a manager with Anvisa told Goulart that they would almost certainly go ahead with the proposal, likely to be formally announced this year, he said.

“In the final round, they will tell us what was accepted and what was not accepted, but I’m sure that refurbished equipment from abroad will not be accepted,” Goulart said by phone.

An exception to the rule might be carved out for hospitals. In Brazil, a hospital that wants to sell a piece of equipment to another hospital must first get the equipment refurbished, Goulart said. This could require sending the equipment back to the manufacturer (abroad) to have it fixed up, and then brought back into the country for the sale.

While it’s possible Anvisa might make an exception for these hospitals, American companies that have been importing refurbished equipment will likely have to change their strategies. Goulart said he knows of one U.S. firm that could be especially hurt by this. The company brings in used equipment to Brazil, refurbishes it there, and then ships it out to be sold in foreign markets.

“We asked (Anvisa) to allow this, because they are creating jobs in Brazil. They are fostering the knowledge of manufacturing,” he said. “We don’t know if they will accept (this kind of) importation.”

You probably have never heard of Contagem, Brazil, an industrial town of some 627,000 souls about 277 miles north of Rio de Janeiro. But there, on July 22, 2010, GE Healthcare opened its first factory in South America.

For now, the plant is making an X-ray system that’s meant to be sold throughout the continent. Soon though, GE also hopes to produce higher-end equipment at the factory, including PET, CT and MRI scanners.

GE isn’t alone in moving to Brazil. Manufacturers of all kinds are headed there, hoping to gain a foothold in the world’s fifth most populous country. After all, Brazil has 400,000 hospital beds. The patients filling those beds are, increasingly, a bit older and a bit richer, and they want access to the same top-flight medical devices the developed world takes for granted.

For foreign companies, this vast nation – the world’s ninth largest – is attractive for many reasons. For one, it has weathered the economic doldrums better than most developed countries, with its gross domestic product forecasted to grow around 4 percent this year, according to Espicom, a market research firm. For another, the market is huge: the biggest for medical devices in Latin America, and the largest private insurance market, aside from the United States, in all of the Americas.

True, compared to the United States, the amount spent on health care per person is low — roughly one-tenth what it is here. Per capita health expenditures are $734, compared with $7,410 per capita in the U.S. (2009 figures), according to the World Bank. Health care accounts for 8 percent of Brazil’s GDP —slightly less than half of what it is in the U.S. Life expectancy at birth is also lower — 73 for Brazil versus 78 for the U.S., much of it owing to tragically high infant mortality rates, especially in rural areas.

In fact, the rural-city divide characterizes much of Brazil’s health care system. Brazil’s partly public system, on which much of its populace relies, has a low doctor-to-patient ratio, especially in the countryside. But Brazil is committed to modernizing its health infrastructure. And with growing wealth, the private sector is increasing in scope. Nearly every month, a brand-spanking new facility pops up, or a hospital announces it has outfitted a new surgical suite or imaging center, with many of these developments tracked by Hospitalar, an organization that runs a yearly conference on health care and hospital business in the country. In December, for instance, Hospitalar reported that 11 private hospitals in São Paulo were receiving $1.4 billion in investments over the next five years. One of these hospitals, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, plans to spend half a billion dollars over the next two years to expand its main facility and open a new branch.

Manufacturers see opportunity

The growth is borne out by the numbers. Between 2003 and 2006, Brazil’s diagnostic imaging and monitoring equipment market grew 20 percent per year, while in the rest of the world it only grew 4 to 5 percent per year, Steve Rusckowski, CEO of Philips Medical Systems, explained in a statement a few years ago.

How big is the market? It depends on who’s reporting the numbers. Estimates for Brazil’s medical device market are around $3.6 billion to $4 billion, according to two Espicom reports from this year. Imports total about $1.8 billion, according to Espicom, although Hospitalar puts that figure much higher ($3.65 billion).

As expected, the country mainly relies on imports for high-tech equipment that can’t be made locally, with the majority of that equipment coming from North America or Western Europe.

Of course, exporting to Brazil isn’t the only path for making inroads into the economy. Companies like GE are making investments locally too. GE’s Contagem factory, for instance, will cost the company $50 million over the next 10 years. GE Healthcare’s parent business also plans to open a massive Global Research Center in Rio de Janeiro next year.

Other manufacturers are planting roots in Brazil. Philips has purchased a number of local businesses to expand its influence there. Last year, it bought Wheb Sistemas, a clinical informatics systems company. In 2008, it bought Dixtal Biomédica e Tecnologia, a maker of patient monitors used in hospitals. But one of its biggest moves was in 2007, when it bought the country’s largest X-ray manufacturer, VMI-Sistemas Medicos, as part of a plan to seize on emerging markets that had been in the works since the previous year. In 2008, the company also opened, in Brazil, the first plant for making MRIs in all of Latin America, according to Espicom.

Siemens Healthcare also says it plunked $50 million in the country last year. Siemens, which says it employs 10,000 people in the country, also intends to invest $600 million in business activities there over the next five years, according to an interview between health care division’s global CEO Hermann Requardt and the Brazilian daily paper DCI. For the past 10 years, Siemens has made the MULTIX B X-ray system in the country, and sold about 750 units, he said in the interview. Now, nearly a third of all digital diagnostic imaging in Brazil is performed on its equipment, Requardt said.

Used dealers need not apply

Although a big market, and one that is “value-conscious” when compared to the U.S. or other developed countries, Brazil is surprisingly off-limits to one class of sellers: used equipment dealers.

In a recent report, the Commerce Department placed Brazil on its list of 16 countries that in some cases have restrictions "so severe as to be tantamount to a prohibition." Thanks to regulation passed in 2001, the RDC 25/2001, in order to be imported into Brazil, used devices must be registered, licensed and refurbished back to original manufacturer specifications, as well as passed through local quality control tests.

"OEMs can bring their products to Brazil easily, such as Phillips, GE, Siemens, since they have a better control on how to refurbish [that] equipment," an official who works with the Commerce Department told DOTmed News earlier this year. "One of the main regulations is that the company that will export to Brazil must have an authorization from the OEM to sell in our country. But even this way, this is still a difficult procedure."

And while Brazil has allowed refurbished equipment to be imported, even that is changing. Carlos Goulart, the head of trade group Abimed, told DOTmed News that Anvisa, Brazil’s equivalent of the Food and Drug Administration, is worried that even refurbished devices aren’t safe. This summer, Anvisa floated a proposal that would completely ban refurbished imports. In acknowledgement of the proposal, the public sent Anvisa almost 1,000 responses, Goulart said. But it seems nothing will sway them. Last week, a manager with Anvisa told Goulart that they would almost certainly go ahead with the proposal, likely to be formally announced this year, he said.

“In the final round, they will tell us what was accepted and what was not accepted, but I’m sure that refurbished equipment from abroad will not be accepted,” Goulart said by phone.

An exception to the rule might be carved out for hospitals. In Brazil, a hospital that wants to sell a piece of equipment to another hospital must first get the equipment refurbished, Goulart said. This could require sending the equipment back to the manufacturer (abroad) to have it fixed up, and then brought back into the country for the sale.

While it’s possible Anvisa might make an exception for these hospitals, American companies that have been importing refurbished equipment will likely have to change their strategies. Goulart said he knows of one U.S. firm that could be especially hurt by this. The company brings in used equipment to Brazil, refurbishes it there, and then ships it out to be sold in foreign markets.

“We asked (Anvisa) to allow this, because they are creating jobs in Brazil. They are fostering the knowledge of manufacturing,” he said. “We don’t know if they will accept (this kind of) importation.”