It will take more than the first cyberattack-related death for healthcare’s security wakeup call

February 15, 2021

By Seth Carmody

This isn’t theoretical anymore.

The global pandemic has accelerated the number of devices deployed to operate outside of the hospital walls, providing remote patient monitoring and telehealth. This has expanded healthcare’s attack surface resulting in healthcare experiencing more attacks . But has this increased attack surface hurt patients? Tying adverse clinical outcomes to security events is hard . Security events such as ransomware typically result in disruption of operations, news of redirecting emergency vehicles and doctors resorting to pen and paper during cyber attacks are prevalent. Disruptions to operations create other issues and delays in care can result in patient harm therefore it wouldn’t be a stretch to postulate that security events have had negative patient outcomes. However, despite numerous ransomware reports, no direct link of a security event to a patient death had been observed until September 2020 where the first patient death linked to ransomware-induced by delay of care was reported. The hospital was unable to take in emergency patients because of the attack, and the patient was redirected to another hospital 20 miles away.

Why is this the first reported case of patient harm? For medical devices, an outdated regulatory model and lack of data due to limited logging capability and monitoring of devices, are reasons why it is so hard to confirm the relationship between a cybersecurity event and patient outcomes. This limited data also makes it difficult to establish a baseline of security requirements that would be sufficient for medical devices. These technologies serve a critical clinical purpose but underserve security; why?

State of the healthcare industry - why cybersecurity isn’t prioritized effectively

The tension between healthcare and security is rooted in the fact that healthcare’s first job is to deliver healthcare. Therefore technologies built to serve healthcare are built primarily to deliver on healthcare features, not security features, like monitoring, that would help connect security events with patient outcomes. As a result, the healthcare industry accrues security debt yet paradoxically, healthcare must also deliver healthcare securely because any lack of security threatens the ability of the healthcare ecosystem to function. This tension must be resolved for any additional progress to occur.

Current attempts to incentivize security economically include HIPAA. However, the incentive is fine based and focuses, not on security debt relief, but on the management of the risk that security debt brings. However, data shows that breaches are increasing, in other words, we’re not any better at security, why? Because the hospital is the least empowered to reduce security debt from the technology it must consume to deliver healthcare. Some efforts tried to tackle leveraging economic incentives by enforcing security requirements before technology is purchased. While these efforts have catalyzed some progress, healthcare’s priority is healthcare therefore, limiting clinical technology purchases because of security debt is necessary yet insufficient.

Additionally, security is hard and requires dedicated resources and deep specialization. Despite spending $10-20 billion on cybersecurity , healthcare lacks sufficient resources to get it right. Especially considering that in some cases it’s healthcare versus nation-states. Should it be private companies’ responsibility to defend against nation-state attacks just because they’re cybersecurity-related? Would private industries be responsible for defending against a kinetic nation-state attack? Of course not, so why is cybersecurity different? Why do we shame and fine hospitals for security practices? Even well incentivized and financed industries with deep specialization, struggle. Look no further than finance and defense. Even the NSA has had its own struggles with security . If security isn’t kind to the security industry, why should we put the burden on healthcare? What will it take for us to understand the magnitude of the challenges before healthcare and take the necessary steps to address the issue? So we put businesses in a situation where they have to make choices about devoting resources to their primary business or spending enormous resources on being proactive for security in a technical deep discipline; the data show that we get worse security and worse healthcare.

What have we observed?

Technologies built to serve healthcare are built primarily to deliver on healthcare features, not security features including monitoring that would help connect security events with patient outcomes. Since devices typically aren’t equipped to monitor and detect security issues, only indirect means are utilized. In an attempt to find a quantitative way of measuring cybersecurity progress, we turn to the regulatory body. The FDA’s Postmarket Cybersecurity Guidance (December 2016), encouraged device vendors to participate in cyber risk information sharing through a variety of ways, such as through FDA safety communications, ICS-CERT, or information sharing entities that share medical device vulnerability information such as the H-ISAC and Medical Device Information Sharing Analysis Organizations (ISAOs).

Two of the presumed benefits of information sharing are that 1) industry stakeholders have the information necessary to minimize their cybersecurity risk and 2) other medical device vendors can use this information to prevent their products from having the same or similar vulnerabilities.

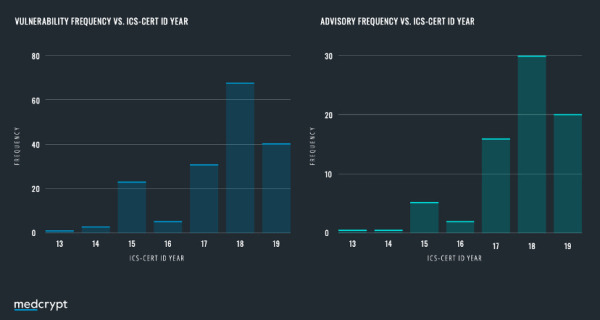

An analysis of the ICS CERT database reveals that device vendors reported a more than five-fold increase in disclosed vulnerabilities since the release of the FDA premarket guidance was released. A hypothesis presents itself here - has there been an increase in the number of vulnerabilities in devices? Or has the assistance of FDA guidance encouraging information sharing helped the industry move up the cybersecurity maturity curve?

The truth likely lies somewhere between the two, but it is important to note that disclosures indicate an active product security function. There are still many device manufacturers that have yet to disclose a single vulnerability, despite having the same vulnerabilities others have already disclosed. We applaud those device vendors that are actively engaged in the ecosystem! And anticipate that once the FDA Premarket Cybersecurity Guidance (October 2018) is finalized (anticipated in 2021), disclosures will increase another 4x.

Path forward

We need laws that incentivize the builders of technology, not the consumer. We also need technology components that are secure by design as well as easily implementable and maintained.

The healthcare industry has made tremendous progress and that must be acknowledged. The issuance of multiple guidance documents from international regulatory bodies and industry leaders, and the voluntary engagement by device vendors and security researchers at the DefCon Biohacking Village, are signs that times are changing. Collaboration between MDMs and external stakeholders such as DHS and security researchers, demonstrates a shift in culture in which sharing and discussing vulnerabilities is not something to conceal, but a sign of maturity and something to encourage.

Healthcare companies are challenged with determining how to continue to innovate and deliver clinical therapies, but doing so while being secure. Until now, the burden has relied heavily on healthcare delivery organizations to ensure devices are operating in a secure environment. Going forward, relying on network security as a primary defense is both impractical for devices operating out of the field, and insufficient for those that remain inside the hospital.

Developing a proactive strategy to ensure security is designed into a device from the inception of the product development lifecycle is the best bet we have at moving the need to ensure patient safety through medical device cybersecurity.

About the author: Seth Carmody is the Vice President of Regulatory Strategy at MedCrypt. Prior to MedCrypt, Carmody worked as the cybersecurity program manager in the Office of the Center Director, Emergency Preparedness/Operations & Medical Countermeasures, within the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)'s Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH).

This isn’t theoretical anymore.

The global pandemic has accelerated the number of devices deployed to operate outside of the hospital walls, providing remote patient monitoring and telehealth. This has expanded healthcare’s attack surface resulting in healthcare experiencing more attacks . But has this increased attack surface hurt patients? Tying adverse clinical outcomes to security events is hard . Security events such as ransomware typically result in disruption of operations, news of redirecting emergency vehicles and doctors resorting to pen and paper during cyber attacks are prevalent. Disruptions to operations create other issues and delays in care can result in patient harm therefore it wouldn’t be a stretch to postulate that security events have had negative patient outcomes. However, despite numerous ransomware reports, no direct link of a security event to a patient death had been observed until September 2020 where the first patient death linked to ransomware-induced by delay of care was reported. The hospital was unable to take in emergency patients because of the attack, and the patient was redirected to another hospital 20 miles away.

Why is this the first reported case of patient harm? For medical devices, an outdated regulatory model and lack of data due to limited logging capability and monitoring of devices, are reasons why it is so hard to confirm the relationship between a cybersecurity event and patient outcomes. This limited data also makes it difficult to establish a baseline of security requirements that would be sufficient for medical devices. These technologies serve a critical clinical purpose but underserve security; why?

State of the healthcare industry - why cybersecurity isn’t prioritized effectively

The tension between healthcare and security is rooted in the fact that healthcare’s first job is to deliver healthcare. Therefore technologies built to serve healthcare are built primarily to deliver on healthcare features, not security features, like monitoring, that would help connect security events with patient outcomes. As a result, the healthcare industry accrues security debt yet paradoxically, healthcare must also deliver healthcare securely because any lack of security threatens the ability of the healthcare ecosystem to function. This tension must be resolved for any additional progress to occur.

Current attempts to incentivize security economically include HIPAA. However, the incentive is fine based and focuses, not on security debt relief, but on the management of the risk that security debt brings. However, data shows that breaches are increasing, in other words, we’re not any better at security, why? Because the hospital is the least empowered to reduce security debt from the technology it must consume to deliver healthcare. Some efforts tried to tackle leveraging economic incentives by enforcing security requirements before technology is purchased. While these efforts have catalyzed some progress, healthcare’s priority is healthcare therefore, limiting clinical technology purchases because of security debt is necessary yet insufficient.

Additionally, security is hard and requires dedicated resources and deep specialization. Despite spending $10-20 billion on cybersecurity , healthcare lacks sufficient resources to get it right. Especially considering that in some cases it’s healthcare versus nation-states. Should it be private companies’ responsibility to defend against nation-state attacks just because they’re cybersecurity-related? Would private industries be responsible for defending against a kinetic nation-state attack? Of course not, so why is cybersecurity different? Why do we shame and fine hospitals for security practices? Even well incentivized and financed industries with deep specialization, struggle. Look no further than finance and defense. Even the NSA has had its own struggles with security . If security isn’t kind to the security industry, why should we put the burden on healthcare? What will it take for us to understand the magnitude of the challenges before healthcare and take the necessary steps to address the issue? So we put businesses in a situation where they have to make choices about devoting resources to their primary business or spending enormous resources on being proactive for security in a technical deep discipline; the data show that we get worse security and worse healthcare.

What have we observed?

Technologies built to serve healthcare are built primarily to deliver on healthcare features, not security features including monitoring that would help connect security events with patient outcomes. Since devices typically aren’t equipped to monitor and detect security issues, only indirect means are utilized. In an attempt to find a quantitative way of measuring cybersecurity progress, we turn to the regulatory body. The FDA’s Postmarket Cybersecurity Guidance (December 2016), encouraged device vendors to participate in cyber risk information sharing through a variety of ways, such as through FDA safety communications, ICS-CERT, or information sharing entities that share medical device vulnerability information such as the H-ISAC and Medical Device Information Sharing Analysis Organizations (ISAOs).

Two of the presumed benefits of information sharing are that 1) industry stakeholders have the information necessary to minimize their cybersecurity risk and 2) other medical device vendors can use this information to prevent their products from having the same or similar vulnerabilities.

An analysis of the ICS CERT database reveals that device vendors reported a more than five-fold increase in disclosed vulnerabilities since the release of the FDA premarket guidance was released. A hypothesis presents itself here - has there been an increase in the number of vulnerabilities in devices? Or has the assistance of FDA guidance encouraging information sharing helped the industry move up the cybersecurity maturity curve?

The truth likely lies somewhere between the two, but it is important to note that disclosures indicate an active product security function. There are still many device manufacturers that have yet to disclose a single vulnerability, despite having the same vulnerabilities others have already disclosed. We applaud those device vendors that are actively engaged in the ecosystem! And anticipate that once the FDA Premarket Cybersecurity Guidance (October 2018) is finalized (anticipated in 2021), disclosures will increase another 4x.

Path forward

We need laws that incentivize the builders of technology, not the consumer. We also need technology components that are secure by design as well as easily implementable and maintained.

The healthcare industry has made tremendous progress and that must be acknowledged. The issuance of multiple guidance documents from international regulatory bodies and industry leaders, and the voluntary engagement by device vendors and security researchers at the DefCon Biohacking Village, are signs that times are changing. Collaboration between MDMs and external stakeholders such as DHS and security researchers, demonstrates a shift in culture in which sharing and discussing vulnerabilities is not something to conceal, but a sign of maturity and something to encourage.

Healthcare companies are challenged with determining how to continue to innovate and deliver clinical therapies, but doing so while being secure. Until now, the burden has relied heavily on healthcare delivery organizations to ensure devices are operating in a secure environment. Going forward, relying on network security as a primary defense is both impractical for devices operating out of the field, and insufficient for those that remain inside the hospital.

Developing a proactive strategy to ensure security is designed into a device from the inception of the product development lifecycle is the best bet we have at moving the need to ensure patient safety through medical device cybersecurity.

About the author: Seth Carmody is the Vice President of Regulatory Strategy at MedCrypt. Prior to MedCrypt, Carmody worked as the cybersecurity program manager in the Office of the Center Director, Emergency Preparedness/Operations & Medical Countermeasures, within the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)'s Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH).